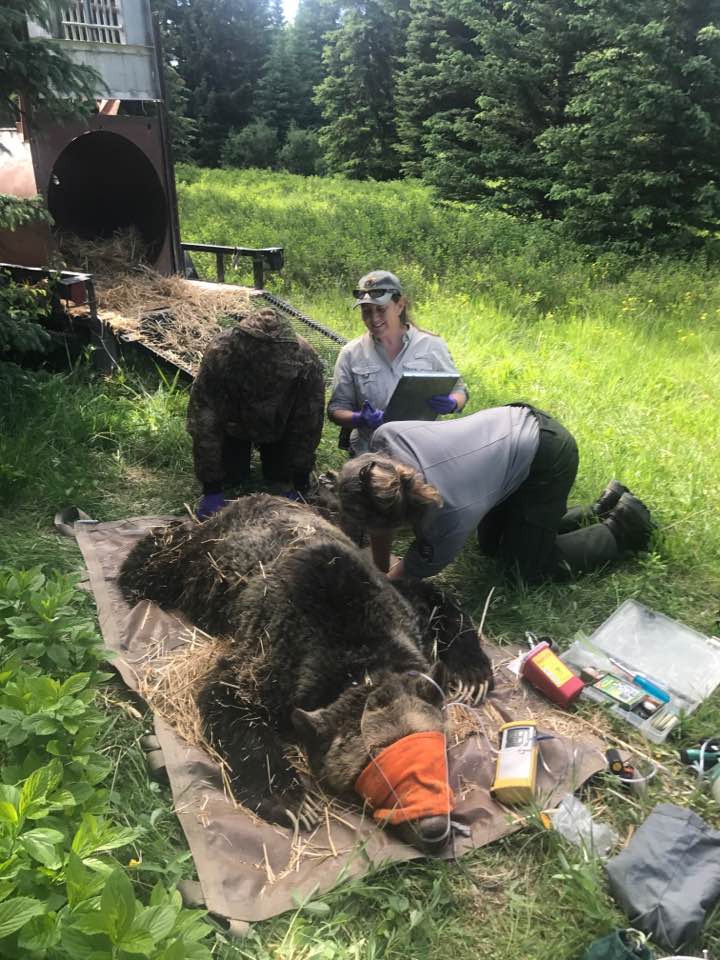

Grizzly bears have expanded in abundance and distribution in Montana in recent years. This enhances the long-term prospects for population sustainability by increasing the likelihood of connectivity between recovery zones. However, because grizzly bears can damage property and injure people, their closer proximity to human habitation poses new challenges for Montanans.

This map shows the estimated occurrence of grizzly bears within Montana as of 2024. The area of occurrence shows watersheds where scattered verified observations have been recorded.

Above: Five Grizzly Bear Ecosystems, estimated occupied range as of 2022, and extent of occurrence as of 2024. Grizzly bears are not equally common in all areas, particularly outside of ecosystem boundaries.

While grizzly bear populations have increased in numbers and range extent over the past several decades, populations are relatively isolated from other ecosystems, particularly within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. This isolation hinders the genetic diversity and overall health of populations. Additionally, natural recovery into the Bitterroot Ecosystem will likely be required to help recover bears in this area, which currently has no known population following extirpations in the 1900s.

A study published in 2023 (Sells et al.) identified potential pathways for male and female grizzly bears to disperse among populations. Using information from 65 GPS collared grizzly bears monitored in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem from 2003 to 2020, the researchers modeled how bears use the landscape relative to physical habitat characteristics and human presence. Results of the modeling indicate that bears have a variety of routes to move between ecosystems and observations of bears between the ecosystems generally support the model results.

GPS tracking technologies enable this type of population study and ultimately provide information for wildlife managers to make informed decisions about habitat conservation and efforts to minimize conflict with dispersing animals. Grizzly bears exist in low densities outside of their established range, but there is a chance of encountering a grizzly bear anywhere in western Montana.

Above: Predicted (modeled) female grizzly bear dispersal routes (Sells et al. 2023) with blue areas representing the most likely routes for a grizzly bear to successfully travel from one ecosystem to the other. Also shown are estimated locations of “outliers” in this area from 2010 – 2023, which were verified sightings or sign of grizzly bears observed beyond current distributions at the time (red stars). Simulation results for males were broadly similar (see below).

Note: These are not confirmed dispersal pathways, but rather the areas most likely to provide the habitat suitable for a bear to move through. Other pathways are available and bears behave independent of one another. Red stars represent verified sightings or sign of grizzly bears observed in this area beyond current distributions at that time, from 2010 – 2023.

Above: Predicted (modeled) male grizzly bear dispersal routes (Sells et al. 2023) with blue areas representing the most likely routes for a grizzly bear to successfully travel from one ecosystem to the other.

The research team’s dispersal route predictions in these first two maps build on previous work by Peck et al. (2017) using simulations that provide simulated bears a start and end point of travel (i.e., from one population to another). This provides useful maps of predicted dispersal routes. However, this method entails the assumption that a bear knows where it ultimately aims to go (i.e., to the endpoint in another population). To alleviate this assumption, Sells et al. (2023) also simulated movements without a predetermined endpoint. These maps provide alternative predictions for movement and habitat use that also align strongly with the known outlier locations in these areas.

Above: predicted habitat use by female grizzly bears beyond existing Ecosystems. This version simulated movements of females without a predetermined endpoint (whereas the first set of maps above provided the simulated bears with these endpoints in adjacent populations). Results for males were broadly similar (see below).

Above: predicted habitat use by male grizzly bears beyond existing Ecosystems. This version simulated movements of males without a predetermined endpoint (whereas the first set of maps above provided the simulated bears with these endpoints in adjacent populations).

For more information, visit https://www.umt.edu/coop-unit/sellslab/sells-research/grizzly-bears.php or https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110199. Pathways data can be downloaded at https://doi.org/10.5066/P91EWUO8.