5 Fun Facts about Bats!

Wildlife Wednesday

Corie Rice at Montana WILD shares her 5 favorite facts about bats. How many did you know?

Montana is home to 15 different species of bats. These bats range in size from the tiny western small-footed myotis weighing in at just 5 grams (that is 5 sugar packets) to the larger hoary bat weighing in around 25 grams. Regardless of their size, all bats need lots of insects to survive, including those pesky mosquitos.

The agricultural pest control service of bats in Montana is valued at $680 million dollars/year. Yet, bats everywhere are threatened by habitat loss, pesticide use, and a new disease called white-nose syndrome that has killed 6 million bats in eastern states.

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks works to conserve bats and their important role in our ecosystem through disease prevention, habitat conservation, and species monitoring.

Rabies is a fatal but preventable viral disease. It can spread to people and pets if they are bitten or scratched by a rabid animal. In the United States, rabies is mostly found in wild animals such as bats, raccoons, skunks, and foxes.

You can't get rabies from bats flying around in your yard. Less then 1% of all bats are found to have rabies. Human exposure to rabies is usually due to accidental or careless handling of bats.

If you believe you may have been exposed to rabies, contact your health care provider or your local county health office immediately.

Learn more from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Learn more at the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services

Rabies can only be transmitted through a bite or from bat saliva entering a cut or wound. Every bat bite or contact must be considered a potential exposure to rabies.

If there has been an encounter, wash the area with soap and water then seek medical attention.

Capture the bat, alive if possible, and don't damage the head. If the bat is dead, keep it in a clean jar in the refrigerator (not the freezer) until it is submitted for rabies testing.

Bats should never be touched with bare hands.

Avoid bats that display abnormal behavior such as those found active during the day or are unable to fly.

Teach children to never pick up a bat. Have all dogs and cats vaccinated for rabies.

Prompt vaccination after exposure can prevent the disease in humans. Rabies shots are no longer the painful ordeal they once were. They are usually given in the arm, and are no more painful than a tetanus shot, but they are very expensive. Testing the bat is the best way to know if shots are needed.

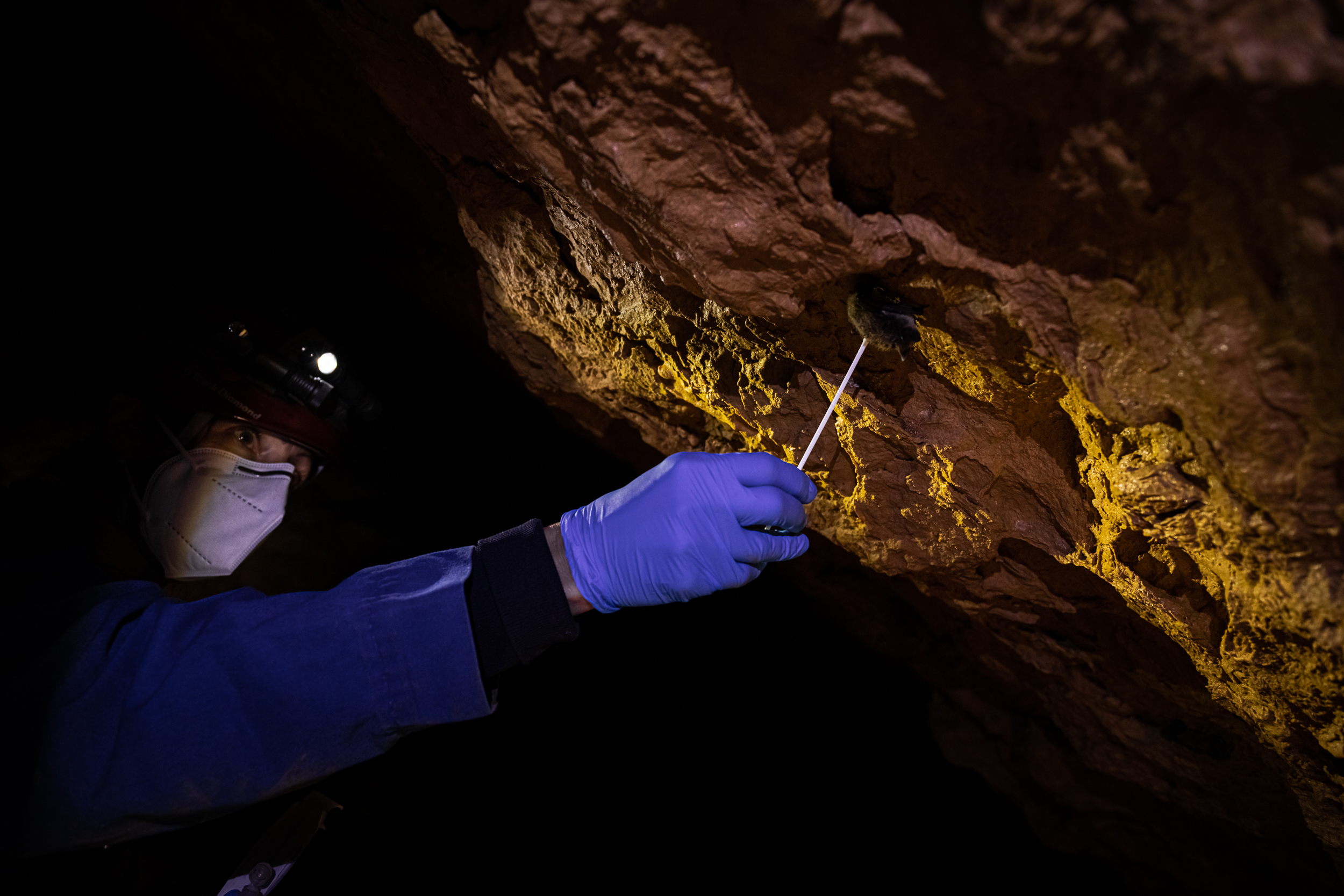

White-nose syndrome (WNS) is a disease that affects hibernating bats and is caused by a fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, or Pd for short. Sometimes Pd looks like a white fuzz on a bat's face, which is how the disease got its name. Pd grows in cold, dark and damp places. It attacks the bare skin of bats while they’re hibernating in a relatively inactive state. As it grows, Pd causes changes in bats that make them become more active than usual and burn up fat they need to survive the winter. Bats with WNS may do strange things such as fly outside in the daytime in the winter.

April 23, 2021 — First Montana case of White-nose syndrome detected in Fallon County bat

January 2021 — Fungus that causes White-nose Syndrome Found in Eastern Montana

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks is taking a proactive approach to detection and prevention of WNS. WNS is associated with massive bat mortality in the northeastern and mid-Atlantic United States and since the winter of 2006–2007, bat population declines ranging from 80–97% have been documented at surveyed hibernacula that have been most severely affected. Although exact numbers are difficult to determine, biologists estimate that losses may exceed 2 million bats since 2007. This mortality represents the most precipitous decline of North American wildlife caused by infectious disease in recorded history.

Without assistance, the one or two biologists serving as WNS "leads" in many states will soon become overwhelmed. Consequently, effective readiness, mitigation, and rapid response efforts for WNS will be significantly compromised. Given the current rapid rate of spread of this malady, it is imperative that more states receive critical funding and coordinated attention, which will result in increased preparedness when/if WNS affects more sites, more states, and more species of bats.

FWP and the Montana Natural Heritage Program (MNHP) have actively engaged with existing and emerging WNS networks—connecting state agency personnel with the broader national network of partner state and federal agencies and nonprofits, as well as private landowners and recreational caving interests that can provide critical assistance.

Partners are developing coordinated early detection and diagnosis measures and taking all steps possible to prevent WNS from affecting Montana sites known as roosts for large concentrations of state-protected bats.

Shannon Hilty

State Bat Biologist

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks

Dan Bachen

Senior Ecologist

Montana Natural Heritage Program

Members of the Northern Rocky Mountain Grotto and Bigfork High School Cave Club have been critical to the collection of data on Montana caves and cave resources to include bats.

Montana's 2023 Annual White-nose Syndrome Surveillance Report (PDF)

Montana's 2022 Annual White-nose Syndrome Surveillance Report (PDF)

Montana's 2021 Annual White-nose Syndrome Surveillance Report (PDF)

Estimating occupancy for Montana bat species prior to the arrival of white-nose syndrome (PDF)

2015 State Wildlife Grant REPORT - Montana Surveillance of Cave and Bats (PDF)

Financial support for this work has been provided by: State Wildlife Action grant federal dollars, matching FWP dollars, and Montana Natural Heritage Program, US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service funds. Volunteer hours at a value of more than $20,000 have been contributed through volunteer monitoring of cave conditions and bat use of caves across Montana in the highest risk areas.

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks has prepared these recommendations to answer common questions on the potential impacts of wind energy facilities to bat populations, and to provide consistent recommendations on how to minimize this risk. FWP biologists worked closely with biologists at the Montana Natural Heritage Program to include data on Montana bat populations and craft recommendations based on bat ecology. This document has been endorsed by the multi-agency Montana Bat Working Group. The recommendations in this document are based on the current best available science and may be subject to change as new research emerges. There is no regulatory authority to require these recommendations and implementation is voluntary.

Montana's 2023 annual white-nose syndrome surveillance and bat monitoring report (PDF)

Post-construction monitoring at Spion Kop Wind Farm 2015-2017 (PDF)

Post-construction monitoring plan for Spion Kop Wind Farm (PDF)

For additional research reports, visit the Montana Natural Heritage Program website

Wildlife Wednesday

Corie Rice at Montana WILD shares her 5 favorite facts about bats. How many did you know?